Builders and Defenders

Welcome to the Builders and Defenders Database

Featured Sources

About Fort Negley...

On the top of St. Cloud Hill in Nashville, Tennessee sits Fort Negley, the Civil War era Union fortification built by enslaved and free Black people. Many had self-emancipated from neighboring states, running toward Union lines in Tennessee and enlisted to help the war effort. Others were offered up by enslavers sympathetic to the Federal cause or hoping for an additional paycheck. Others still were forced from homes and churches by the military and impressed in the building process, and another group came voluntarily in exchange for wages. Together they were around 4,000 strong and built all of Nashville’s fortifications and defenses. Shortly after, around 13,000 Black soldiers of the USCT defended Fort Negley and the city in the Battle of Nashville, among the Civil War’s final deciding conflicts.

About the Battle of Nashville...

Over 15,000 Black soldiers enlisted in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) successfully defended Fort Negley during the Battle of Nashville in December 1864. The soldiers came from diverse places and wide-ranging experiences. A majority of them were formerly enslaved men originally from Nashville and Middle Tennessee. Others from the Deep South self-emancipated and sought freedom by running to Union lines in Nashville from states like Alabama, Louisiana, and Georgia. Still others enrolled in USCT regiments from northern states and who were assigned to defend Nashville. As this famous lithograph depicts, Black soldiers chased Confederate troops out of Tennessee and, in doing so, they were the key, instrumental forces behind Union victory at the Battle of Nashville - risking everything in one of the Civil War’s last deciding battles for their freedom.

In the News...

Descendant Stories...

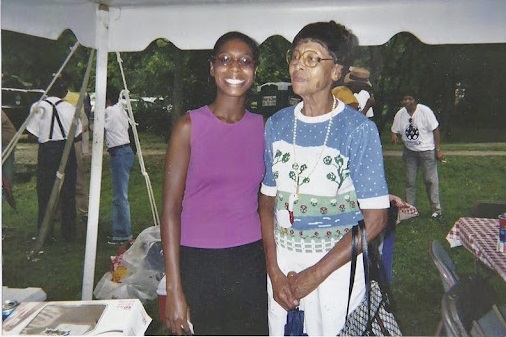

Dr. Eleanor Fleming, Descendant of Ruffin and Egbert Bright

Dr. Eleanor Fleming was born and raised in Williamson County where she was surrounded by the history and memorabilia of the Civil War. Although Fleming never considered Nashville home, she always considered it a home away from home because most of her educational training took place in Nashville at Vanderbilt and Meharry Medical College. Fleming’s grandmother was the genealogist of the family, and she told many stories about the family when Fleming was growing up.

In 2017, the Fort Negley Visitors Center tweeted the names of the impressed black laborers that built and defended Fort Negley and other fortifications in Nashville from the Employment Rolls and Nonpayment Rolls of Negroes Employed in the Defenses of Nashville, Tennessee. It was through these tweets that Fleming discovered that her paternal ancestors, Ruffin and Egbert Bright, had a connection to Fort Negley. “And from there, it became this adventure of kind of rediscovering myself, by discovering Ruffin and Egbert.”

Gary Burke, Descendant of Peter Bailey

Burke’s father served in the Korean war, and his grandfather fought in WWI. Burke’s late father left him documents tracing their family’s ancestry. Burke was surprised when he saw records dated from the Civil War, and one of the War Department records stated on the backside “grandmother receiving pension from the Civil War”. After six years of being a living history interpreter, Burke discovered that he was the great-great-grandson of Peter Bailey, a private with Company K, the 17th Regiment of the United States Colored Troops.

Private Peter Bailey was stationed at Fort Negley during 1864 and 1865. He was 5’8” and only eighteen years old when he entered the Civil War. Private Bailey fought in two engagements, Granbury’s Lunette and Peach Orchard Hill, while living through terrible conditions to secure the future of his descendants, and Burke holds that bravery close to his heart. Burke visited Private Bailey’s gravesite in Lincoln Cemetery in Chicago, Illinois where he placed a Sons of Union Veteran marker on his final resting place to honor his legacy. “I was already fighting a battle against ignorance about African Americans who served in the Civil War. And then, to find out my own flesh and blood did it was gratifying.”

The Johnson Family, Descendants of James Harding, Sr.

The Johnson family, Sabrina Johnson-Gresham, Carmen Johnson, Felix Carlos Harding-Johnson, and Charles Johnson III, learned about their family history from their grandfather William Howard Harding. He often told stories about his grandfather James Harding Senior, who they called grandpa. According to a Nashville Globe article, James Harding Sr. is considered one of Nashville’s oldest residents. Harding Sr. left Belle Meade plantation and joined the 9th Confederate cavalry. He later ran away and joined efforts with the Union Army at Fort Negley where he was a laborer. After the Civil War, he worked as a carpeterner who helped build Fisk University’s Jubilee Hall. James Harding Senior was married to Sallie Harding, and he was the father to sixteen children.

Growing up, the Johnson family took frequent visits to the family’s gravesite to commemorate their memory at Greenwood Cemetery. Purchased in 1930, the family brought eight gravesites where Mike Harding, Sally Harding, James Harding, James Harding Sr., Hiram Harding, Felix Harding, Sadie Harding-Gleaves, and Abraham Gleaves are buried. Charles Johnson III didn’t know that James Harding Sr. was born into slavery until he read the Nashville Globe’s article about James Harding Sr., and Carmen Johnson made the connection after looking at birth certificates when tracing their ancestry. “I did not realize that when he took us there that’s his grandfather. I knew he was born in 1800. I didn’t realize he was born a slave. I didn’t realize his history.”